6 mai - 6/366 - Aujourd'hui pour de semblant

17 avril - 5/366 - Aujourd'hui chaleur de

10 avril - 4/366 - Aujourd'hui tout ce qui brille

24 mars - 3/366 - Aujourd'hui super héros

22 mars - 2/366 - Aujourd'hui le bien le mal

21 mars 1/366 - Aujourd'hui ce qu'il en restera dans un an

Multitrack

All Your Money Are Belong To Us

Ode à tous les instits de la terre

Do You Scale Well?

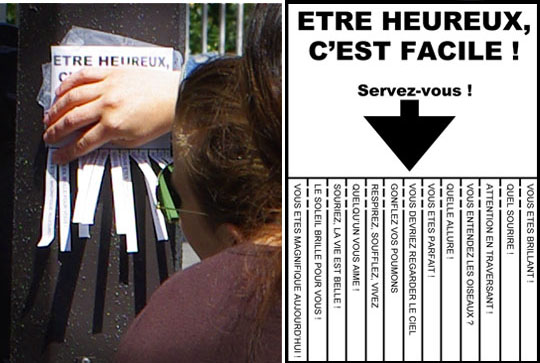

Y'a quand même des gens géniaux...

J'ai mal au clavier

"En charge de" me gave. Grave.

Wikipedia Is Ten Years Old: A Human Adventure

Wikimedia Chapters: We Want to Hire Someone, Where Do We Start? (part II)

Wikimedia Chapters: We Want to Hire Someone, Where Do We Start? (part I)

La lune le jour

Deux-cent quarante huit kilomètres à l'heure

Everything He Sees

29 juin - 7/366 - Aujourd'hui tout le monde ne dit pas merci.

Aujourd'hui tout le monde ne dit pas merci. Moi, si. En ce dernier jour d'école, je dis merci. À vous, Madame, qui vous êtes occupé de ma fille pendant une année scolaire et l'avez rendue plus grande, plus belle, plus forte, plus prête. Merci en particulier de ce geste de tous les matins, lorsque vous vous agenouillez pour regarder dans les yeux nos enfants qui sans vous ne verraient du monde que des jambes.

one comment

-->6 mai - 6/366 - Aujourd'hui pour de semblant

Aujourd'hui on ferait comme si tout allait bien, comme si ma tête s'était remise de cet état second de malade qui m'accompagne depuis dix jours. Aujourd'hui pour de semblant on dirait "tout va bien" et on continuerait à vivre comme si de rien n'était parce qu'après tout, je ne suis que malade, pas morte, ou un truc pire.

17 avril - 5/366 - Aujourd'hui chaleur de

Le printemps s'est acoquiné avec l'hiver et à eux deux ont créé une nouvelle saison. Lumière de printemps et chaleur d'hiver. Il fait moins quelque chose mais le soleil brûle les yeux par le biais du vert tendre des feuilles nouvelles.

10 avril - 4/366 - Aujourd'hui tout ce qui brille

Vu le temps qu'il fait dehors, la seule chose qui brille et brille fort, ce sont les yeux de mon fils quand il dit le mot qu'il a appris ce week-end (Pâques oblige) : "Gouca". Qui veut dire chocolat. Ça change de "Auto" (à prononcer Aouto, à l'allemande) qui a été son unique leitmotiv depuis trois semaines.

24 mars - 3/366 - Aujourd'hui super héros

Aujourd'hui j'ai rêvé que je refaisais le monde.

22 mars - 2/366 - Aujourd'hui le bien le mal

Parfois, ma fille ment. Ou plutôt, parfois, ma fille m'a menti. Ou plutôt, parfois ma fille ne sait pas encore très bien faire la différence entre ce qui est bien (dire la vérité) et ce qui est mal (raconter des craques). Et du coup je ne sais plus distinguer ce qui est bien (la croire si elle dit vrai) de ce qui est mal (la gronder alors qu'elle dit la vérité). C'est ce que je trouve de plus difficile, dans le boulot de parent. Inculquer la justice, et l'honnêteté.

21 mars 1/366 - Aujourd'hui ce qu'il en restera dans un an

Dans un an il ne restera absolument rien de ces bleus qui ornent l'un l'oreille de ma fille (un bleu sur l'oreille, une prouesse, fait par une balançoire) et l'autre le front de mon fils (un bel oeuf, il est bien tombé, le sol était dur). Rien que les photos que j'ai prise pour la postérité et ces quelques mots (moins de cent) qui rappellent que l'humain est fragile.

Multitrack

I've been thinking about how YouTube really is an amazing window on the world lately. Or rather, a window on an amazing world, full of people with talent that I would probably never ever get to discover, all competing for their 15 minutes of fame... I've learned one thing today, what multitrack ist. Basically people record different tracks of a song and then mix them together. Some of them do it also completely a capella (imitating the instruments). And I liked it. Especially those two:

via Embruns

and this one

Try a search on YouTube with "multitrack" as a keyword, there's much to stumble upon.

one comment

-

Super intéressant ces vidéos ! :-)

—

On Tuesday 6 September 2011 at 15:59

All Your Money Are Belong To Us

Stu West, treasurer and vice-chair of the Wikimedia Foundation, published an interesting post about "Fundraising, chapters, and movement priorities", where he asks questions. Sebastian Moleski gives a very thoughtful and rational answer based on the idea of subsidiarity (Subsidiarity as a fundamental principle), one which I subscribe to.

There are however a few comments that come to mind while reading both posts, which I will try to bring to light here. To try and keep some clarity, I will structure this around Stu's questions. Note for those too lazy to read all the other posts (although you really should), we're talking about Wikimedia, and Wikimedia chapters (the national associations that foster free knowledge and support Wikimedia projects).

The infamous 50%: Where do we really need them?

Stu says

The issue is whether our approach to distributing funds to chapters should change along with all the other things that have changed over the past five years. Here are a few key questions I’m asking myself: Is it right that 50% of rich country donations stay in those rich countries?

Sebastian argues (with a few calculations at the top of his head) that the actual amount of donations that stay in the "rich countries" is much more than 50% of the overall money received (which, incidentally, I agree with).

But this conversation right here is a bit awkward, because it seems to me we are mixing apples and oranges. Let's try and remember where those infamous 50% come from. Actually, we don't really know where they come from, but they are the backbone of the fundraising agreement between Chapters and Foundation and have been for a few years. I'll pass on the details, but here is how it works: if 100€ are donated to a chapter, 50€ go to the Foundation, 50€ stay with the chapter. So the latter 50€ are the 50% which Stu says stay in "rich countries".

Well, since this 50% rule only applies to money raised through the chapters, what we're really talking about here are $2.15 million (50% of $4.3 million, which is the amount raised by the chapters), which, indeed do stay in "rich countries". Sebastian points out that if you actually look at the whole (donations to the Wikimedia Foundation included), much more than just 50% of the donations to Wikimedia actually stay in "rich countries". What I genuinely don't understand here, is why and how that would be wrong.

Actual figures are clear, Wikimedia spends most of its money in "rich countries", but if we're going to go that route, the amount that stays in rich countries due to chapters is actually only 7 or 8% of the total (the 2.15 million I mentioned above) 50% of 15% of the total amount of donations received by Wikimedia worldwide. Is that really insane? I personally don't think so. Also, I don't see anytime soon where the Foundation is going to spend 50% or even more than 50% of its revenue in the "Global South". It will, and should, as per the strategic plan, increase its investment there, but whether or when that amount will ever reach 50%+ of the total donations is, at least for now, and until the real need and impact are measured (as suggested by Sebastian), unlikely and/or unknown.

Now for the real question, which Sebastian hints at:

The emphasis on the Global South just started last year and there’s been, so far, no evaluation of how much impact Foundation spending in the area has actually had. We simply don’t know how much money needs to be spent on the Global South in total, or even within the coming year, to achieve the goals set out in the strategy. But if we don’t know that, how are we to decide whether 50% is enough?

How much money do we, as a movement, actually need to invest in the Global South? Stu seems to regret that money is staying in "rich countries" instead of going to the Global South,[1] but it is not clear to me what Wikimedia's investment in the Global South actually needs to be.

Whatever it needs to be, however, the next question is: are we actually short on money to invest? Is the money that stays "in rich countries" through chapters, missing anywhere else? And if that's the case, could it be an option to ask those chapters in rich countries to actually direct some money from their own programs to invest (or support the investments made by the Wikimedia Foundation) in the Global South? I have a hard time imagining that if the money is sorely needed and the programs make sense, a chapter would not consider this option.

Establish solid movement-wide financial controls

Stu asks:

How do we establish solid movement-wide financial controls to protect donor funds?

Sebastian's answer is one I would subscribe to. He points out:

My approach to „how to establish solid movement-wide financial controls“ would be to start conversations between Foundation and chapters both on a set of global minimum standards and a solid and independent reporting/enforcement structure.

The minimum standards are a must, and have been discussed in various places, not least within the development of the Wikimedia Charter started by the Movement Roles project. While the charter probably has a wider scope than just financial, it could actually contain the criteria for financial control needed to ensure our donors' money is used well.

Every time the subject comes back on the table, I can't help thinking about the International Non-Governmental Organisations Accountability Charter, which in my opinion is an excellent basis as to what we could be looking at for Wikimedia. I also started, in the frame of my work in the Chapters Committee, developing a set of chapter assessment criteria that could be used as measurement points somewhere along the line. In any case, I do believe, like Sebastian, that the standards need to be far reaching within Wikimedia, and that all Wikimedia organisations should be held up to them.

Who is ultimately responsible for stewarding donors’ contributions?

Actually, I find this to be the most interesting question of all. I find it interesting that in the past say 4 or 5 years, the question of "Shouldn't the Foundation be the one responsible to ensure transparency, financial control, and actually, complete control?" still is out there. It may be that I am old and remember a time where there was Wikipedia, and a very weak (not to say inexistant) Foundation. Because that's what history says. The Foundation was built to support Wikipedia, as were the Chapters. Wikipedia is not a product (in the generated sense) of the Foundation, nor is it a product of any Wikimedia organisation. As a matter of fact, it was there before all organisations. What I don't understand, and this is a genuine "not understand", is why in all of these conversations, I always have the impression that many Foundation affiliated people, be they staff of board, are under the impression that the money belongs to the Foundation. Does it? If yes, why?

I won't hide that for me, the elephant in the room is that the Wikimedia Foundation today acts both as an international coordinating body and a chapter. Seeing that the only existing chapter in the US is not allowed to fundraise, this makes the Foundation the national entity in the United States, and hence, a chapter by default, if not by design. Which to some extent skews the equation.

I am a strong believer that the money belongs to the projects, and that if an organisation is best placed to steward donations, it is indeed the Foundation, but not the Foundation as it exists. A truly international coordinating body would not actively fundraise in one country or another, since, if we agree with the principle of subsidiarity, a "local" organisation is best placed to do that. It might (and actually should) act as a fundraising recipient in countries where there is no organisation to apply the principle of subsidiarity, but would let local organisations fundraise where they can do it best.

I'll join Sebastian here to say that we (all Wikimedia organisations) are all responsible for stewarding donors' contributions. In a constellation where the Wikimedia Foundation is not a US chapter, but more something like a "Wikimedia International", it could then more easily steward donations and redistribute them appropriately, where needed. Each chapter (US included) would have a duty to finance operations and programs, and do so by giving X (where X could be 50%, 80% or 20% or whatever, depending on designed programs and needs) of the donations originating in their country to Wikimedia International. A truly international coordinating body would also have the necessary political power to develop a binding development strategy, which all entities in Wikimedia would follow. Whether the existing Wikimedia Foundation has that is yet to be confirmed.

I am convinced that having "Wikimedia international" in the US is a good thing for what we're doing (legal frame for hosting providers being one of the strongest points), and also convinced that the chapters should never argue about giving money to keep the projects up and advance the overall mission. But as long as the Foundation is effectively a chapter, I can understand why we're hitting the same wall again and again. After all, color me a French chauvinist, but why should the US rule the world of free knowledge and decide what's best for us all? And here, I am refering to returning intercultural problems in how to fundraise (you just don't fundraise in Germany, the UK, the Philippines, the US or India the same way), how to work on messaging (be it fundraising or overall presentation of who we are and what we are doing), how to develop organisations (should every chapter have an office? To do what?) etc. If, indeed, subsidiarity is king, then "Wikimedia International" should be empowered to make the high level strategical decisions, which local organisations would then have a duty to implement on a local level, and to fund where necessary on a global level (investments in the Global South, for example).

And what I still don't get, is that many other international organisations fundraise on a local level, see for example the WWF which claims on its international page: You can also donate to your local WWF office: they can do more with your donation!

, or SOS Children's Villages which states Please select the country you live in from the list below in order to get tax advantages which could help you to give even more support to help children in need with your online donation.

or again Amnesty which sends you to the local website to donate if there is one. Why couldn't we?

As a sidenote: I understand, and actually share, the concerns about newly formed chapters coming into way too much money in their first years, and this definitely is an attempt at putting together a set of guidelines which will prevent failure and ensure continuity in how chapters develop. But this is not solved by simply saying "All the money must go in one place". And since this post is already way too long, it'll do for another one.

More to read

I'll edit this section to point out posts or comments that I find interesting about this conversation

- Phoebe's conversation appeal: Chapters, fundraising, and “the movement”

- Florence's take on Stu's questions: Wikimedia Foundation, Wikimedia Chapters, Fundraising ... giving less to get more

Note

[1] by the way, I dislike the term "rich countries" almost as much as I dislike the "Global South" thing, but I have found no satisfying alternative

3 comments

-

Jan-Bart De Vreede asks [1]:

I have a question: you keep referring to "amount raised by the chapters"... what is that? Is that money that was donated directly to the chapters in a special fundraiser by the chapters, or is this money that is actually raised by the WMF fundraiser/donation button but donated by people that happened to fall in the geographic location of the chapter?

So lets say we have a country which has no chapter but the citizens of that country donate an average of $100,000 per year because they love wikimedia... once a chapter is formed there... is that money which is now automatically "raised by the chapters" in your view?

----------

Well, I guess this comment comes to prove my point ;), at least some people in the Foundation do think that the money belongs "to the Foundation". So let me try to explain.

When I say "raised by the chapters", I am probably not using the semantically correct phrase. I should say "through" the chapters instead. But I would use the same for the Foundation. Actually, the correct thing would be to say "raised through the projects" and if we wanted to be even more correct,"through Wikipedia". The Foundation has made tremendous progress (and tremendous is not even close to reality) in managing the fundraiser. The chapters have too. Not all of them, and not all of them with the same success, but as far as I know, the fundraiser has been (and the Foundation advertises this too) very much of a collaborative thing. Community, chapters, staff, many people have been working on it for the past few years. Having been a treasurer of a chapter twice, and having followed the fundraiser developments internationally and extremely closely in at least two chapters, I say without hesitation that yes, the chapters have been working very hard at making the fundraiser a success in their own country. The technical infrastructure that allows having a banner at all belongs to the Foundation. However, landing pages and ensuing messaging have been developped by the chapters. So I have to say that I find calling these international and movement wide efforts "the Wikimedia Foundation fundraiser" a bit of a stretch.

While donors may happen to fall in the geographic location of the chapter, I guess that people in exactly the same way "happen to fall in the geographic location of the Foundation", so I don't really see this as a valid argument to brush away the efforts that have been undertaken movement wide to make the fundraiser a success and attribute the success to the Foundation only. Historically, older chapters have managed donors, just like the Foundation, with more or less success, but in the end, the donors return, so the job can't have been done all that badly.

Your second question is a bit trickier, and my sidenote brushes on it. There are (few) countries in which there are lots of donors, and where the donation amount is very important, and where there is no chapter. So indeed, it makes no sense to say that the money has been raised "by the chapter" before they even exist, or on day one of their coming into existence. But while it does not make sense to say that this money has been raised "by the chapters", I don't think it makes sense either to say that this money has been raised "by the Foundation". If anyone, then the community, which has made Wikipedia an amazing resource in this or that language and has provided incentive for donors to support the projects, and maybe (hopefully) the idea behind them. The donors' survey (p.13) does not ask the donors whether or not they're aware of programs supported by the Foundation or Chapters, which is too bad, but in the answers provided and given, the reason why donors give is pretty clear: "To keep Wikipedia free for all users" (90.2%), "To maintain Wikipedia's independence and objectivity" (88.6 %), "Because I feel it’s important to support something [they] use so heavily" (81.1 %) and "To provide access to knowledge to people who otherwise wouldn't be able to afford it" (80.8 %). That last one being clearly about Wikipedia being the vessel for access to knowledge.

So this brings on the question: "Do we actually fundraise succesfully for our mission (which goes way beyond the Wikimedia projects) as organisations?" There are still a lot of tests to make and data to analyze, to see how much of the money comes in because we have fantastic programs or whether it's all about "just" Wikipedia and a nagging banner. Until then, and meaning no offense to those who've been working extremely hard to make the fundraiser happen, be it on the Foundation side, within the community or in the chapters, I don't think that we can say that the money is being raised by "anyone" but the Wikimedia projects. And actually, I think it is how it should be.

[1] Jan-Bart's question was on a thread in Google+, where he put it because he couldn't comment here for some reason. I just copy/pasted.

—

On Wednesday 3 August 2011 at 11:16 -

I have a huge issue with your suggestion the WMF is a US chapter. It not in anyway the US Chapter. It is merely the largest impediment to a US Chapter. That WMF=US Chapter is the last argument anyone from an existing chapter should be making. Right now anyone unhappy about the US situation could blame the WMF just much as the chapters. More actually because the chapters weren't exepted to inherently think of other groups to the same as WMF. But if you really want to push all these unaffilialted Wikimedians into an emotional response against your position continue suggest they are being better served than French Wikimedians, etc. I would imagine that you really don't want to provoke that sort of reaction and weaken your position when you instead you could promote a stronger position for WMFR by championing the underserved Americans being sabatoged by the WMF's greed!!!! Or you could rachet down the rhetoric altogether and negotiate a way to see that ALL parties involved are given the responsibility of stewardship over donations and the ability to be a check against one another. And ensure that one party's position is not made so strong that in the unlikely event of future malfeasance the other parties are obligated to continue funding it.

—

On Saturday 6 August 2011 at 03:52 -

BirgitteSB, first, I want to thank you for the time and thought you give to the issue (foundation-l and here), because I believe it is an important issue. And reading your comment, I see that I have expressed myself badly in that part of my post. So let me try to put everything into context. We are talking here about fundraising, ie. gathering donations. In that regard, I believe that I am not too far from the actual situation. As it is, the WMF is the only organisation that is allowed to fundraise in the US. It's the only organisation that offers tax deductibility to US people. That makes it, in the US, regarding fundraising, as acting as a "national organisation".

What I am trying to say here, and I am largely basing myself on Sebastian's post about subsidiarity, is that the Foundation operates as both a national entity, and an international entity. It's a fact. Not a judgement. Whether it does that job well or poorly wasn't in my post. But since you address it, let me try and comment on your concerns. I agree 100% with you that the Foundation being located in the US is probably the biggest impediment of the US community getting organized in form of a chapter (or even a set of "more local" chapters). The US, by its large geography, already has a disadvantage in comparison to say France or Germany, not to mention the Netherlands, because it is simply harder to get together, and experience proves that getting together goes a long way in shaping a chapter. The Foundation has also been steering projects on US territory (Public Policy Initiative for example), effectively taking away the learning curve from the community to develop such programs. I am not saying that these are bad projects, the results are, at least I find, amazing (see on the Outreach wiki what is going on in the Campus Ambassador program for example).

I really did not mean to hint that the US community is better served by the WMF than communities that might be served by a chapter. In the light of the principle of subsidiarity, I believe that it isn't. As great as the Ambassadors' program may be, I can't help the feeling that it has been used as a springboard for the Global South development axis, and that in that regard, the Foundation is not addressing directly the needs or wishes of the US community, but pursuing a greater "goal", which is alright if the WMF is the head of an international movement, but which is not alright if the WMF is to be the only independant fundraising organisation in the US.

My take is, you can't be at the international level and the local level at the same time and be effective in both. This is exactly what we are experiencing now. The Foundation is trying to be both, and unfortunately, not exactly succeeding at any. Neither the local level (successes exist, but hey are extremely partial) nor the international level (local level is challenging the direction the Foundation is trying to give).

I hope it makes my thoughts clearer.

—

On Wednesday 10 August 2011 at 13:59

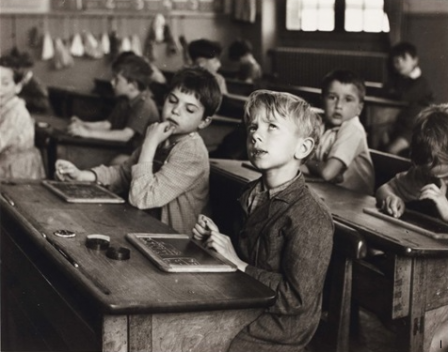

Ode à tous les instits de la terre

Je viens de passer deux heures à la maternelle avec ma fille. Une sorte de galop d'essai pour la rentrée qu'elle effectuera en septembre, histoire de voir comment se déroule la classe et pour lui donner une idée de ce qu'est "l'école" dont on lui rebat les oreilles depuis six mois.

Petite section de maternelle. 23 gamins (vingt-trois). Et moi qui trouve que chez la nounou, cinq gamins c'est déjà compliqué. Vingt-trois gamins. Vous l'aurez compris, je n'en reviens pas. Je n'ai que des souvenirs vagues de la maternelle, peut-être même aucun, sinon ceux que l'on m'a racontés (genre le jour où je suis allée à l'école sans culotte, le jour ou J. m'avait piqué ma petite voiture et où la maîtresse lui avait donné raison quand il lui avait dit que c'était la sienne - premiers stigmates de sexisme ;) etc.). Bref. Du coup, se retrouver en observatrice (participante, parce que ma fille n'a pas pu s'empêcher de venir se réfugier dans mes jambes à un moment ou à un autre) immergée dans une classe de petite section de maternelle, ça vous en apprend un paquet sur la vie.

D'abord, que les enfants sont des êtres à part. De N. super smart qui finit son exercice 10 minutes avant les autres et a un sourire à vous faire tomber raide, à A. un peu moins smart qui a du mal à finir son exercice mais qui a un sourire non moins charmeur, on trouve L., un peu lente, mais surtout qui plane à 12000, M. qui fiche le boxon pendant deux heures, E. et L. qui rêvent d'attention et voulaient à tout prix me montrer leurs cahiers, j'en passe et des meilleures. Les enfants (dans le cas qui nous occupe, tous entre 3 et 4 ans), c'est un peu magique. Mais de là à en avoir vingt-trois...

Le plus dur, j'ai trouvé, c'est le niveau sonore. Soit j'ai des oreilles super sensibles, soit c'est vraiment bruyant, un groupe de vingt-trois enfants. Au bout d'une heure, j'avais les oreilles en compote et ne savais plus où donner de l'ouïe. En suivant, la frustration que doit engendrer la difficulté de se consacrer à tous les enfants. Bon, là, je suis restée deux heures, donc j'imagine que sur le long terme on doit pouvoir répartir un peu l'attention, mais quand même. Pour un même exercice, N. le fait en 5 minutes et A. se bat avec les dominos, les nombres, les gommettes pendant 20 minutes et n'arrive pas à le terminer correctement. On aimerait pouvoir l'aider, mais...

Enfin, ces deux heures m'ont fait prendre conscience d'une chose. Les instits sont eux aussi des êtres à part. Et du coup, je voulais par ce billet remercier tous ceux qui, bons ou mauvais (avoir des mauvais profs fait aussi partie de la vie), ont choisi (ou même n'ont pas choisi) d'éduquer nos enfants. Parce que franchement, vingt-trois gamins, c'est pas une sinécure. Sans compter que j'ai pu avoir une idée de ce que c'est que de se coltiner les quarante et quelques parents de ces enfants-là, qui, tels que je les imagine, remettent en cause chaque décision, chaque exercice, chaque mot... Merci donc, chers instits (et profs, je m'avance, on sait jamais) et je vous promets solennellement d'être une parente modèle et de ne pas vous prendre le chou pour des histoires triviales de lavage de dents, horaires de récré et autres trucs qui tombent sous votre jurisdiction. Je ferai mon boulot de mère à la maison et vous laisserai faire le vôtre, à l'école.

Sources

Photo (super copyrightée, je sais) © Robert Doisneau - École rue Buffon, Paris V, 1956

Do You Scale Well?

So here I am, looking for this blogpost I am positive I wrote one day, and I can't find it. I've looked, really, on both this blog and the other one. But nope, it's not there. Strange. So I guess I'll have to write it. To be fair, I brush upon the topic in this post.

But this Scale Theory of mine is not exactly an intercultural theory per se, it's more of a communication thing, which I developped a long time ago, way before I even thought I'd ever work in trying to understand how people communicate. Anyway. This is a theory about giving (and taking, as I think both are intrinsically linked and can't work without each other, but that could be the topic for another blogpost) and about how giving and taking are highly dependant on language. Not so much language as in French or German (although actual language issues may come into play) but rather language in a "thing I lug around with me when I try to interact with people" kind of way. Something like your expectations, your intent, the meaning you put behind words etc.

To understand the idea, you have to put yourself in a state where you are giving something. This something can be a physical thing (a book, a bunch of flowers, whatever), a hug, or even a word of appreciation. Done that? Good. Now imagine that the "effort" (for lack of a better word) it takes you to give that thing is measured against a scale, your scale. In order to make things easier, we'll decide that this scale of yours has the inch (in) as a unit and that the tool your use to measure it is a 5in ruler. When you give, what you give will be measured against this ruler, and for you, giving 5in is more "important" than giving 1in. The "importance" can be measured by many different values that all converge into this 1 to 5in scale. Values can be, in no particular order: how much that thing has cost you, how difficult it was for you to give it, how complicated it was for you to express it, how often you usually give something like this etc. All of this results in your final measurement.

Now say you give a book. This is a book that is out of print, so really hard to find, and you've loved it a lot because it tells a lot about who you are and what you think. So when you give it to someone (we'll call that someone "deserving-person"), you decide that on your scale, this act of giving is worth a 4. 4 inches on your inner ruler. 4in is a rather big thing on a scale of 5, right? So here you go, giving that book to deserving-person, all happy about yourself and how great a gift you're giving them. And for some reason, deserving-person looks at the book and goes: Oh, thanks.

(you know, with this little undertone that goes "eh, you shouldn't have, and means it litteraly), and that's it. Quite a turn off, right?

So why was deserving-person not quite as excited as you when you gave your gift? Well, my take is the following. While your ruler is expressed in inches, their ruler might be expressed in centimeters. So while your ruler is 5in (approximately 10cm), their ruler is 10 cm long. If you put both rulers side to side, they'd be virtually the same length. What changes is the scaling. So what happens? Deserving-person might have seen the 4, and not gone further. They measured that 4 against their ruler, and it came out to mean 4cm. Not much on a scale of 10. It might be they don't like books, or have three copies of that one, or don't understand why you would offer them a book. Whatever. In the end, the problem lies not so much in what you've given, but in what the other percieves they're getting. And if they stop at the number without looking at the unit, they might get disappointed, because your scaling and theirs are different. Makes sense?

The theory behind this is that we'll take what's given to us and more often than not judge the gift against our personal ruler, without trying to put things in perspective. Your friend hardly ever hugs you? Bummer, you're quite the hugging type and hug them all the time. But then, do they hug anyone else? Ever? Often you'll realise that if you do put things in persepctive, and for a minute put yourself in the other's shoes, you might understand how difficult it was for them to give whatever it was they were giving and feel honored, grateful, happy that they gave precisely this to you. The value of the gift should be measured against their ruler, not yours. It's a damn hard thing to do, but trying it, you're in for really great discoveries. At least, that's what I found.

Sources

Photo by Biking Nikon OGG - "Ruler - Wooden; Why no "Inches" label?" Flickr - CC-BY

Y'a quand même des gens géniaux...

J'ai mal au clavier

Depuis quelques semaines (mois ?) maintenant, la plume me démange. La plume, la vraie. Il y a vingt ans, j'aurais pris mon stylo-Waterman-à-l'encre-bleu-noir et j'aurais écrit une lettre sans queue ni tête à celle-qui-se-reconnaîtra pour lui dire le soleil du printemps qui s'incruste, mes pensées du jour et mes délires de la nuit.

Il y a vingt ans, cependant, je n'aurais pu dire la fatigue liés aux pleurs incessants de mon enfant malade, ou la peur, celle qui tire des larmes, d'être une mauvaise mère parce que je ne sais pas calmer mon enfant qui, ayant fait l'impasse de la sieste, hurle de colère et de fatigue. Il y a vingt ans, je n'étais pas mère.

Mais là n'est pas mon propos, si propos il y a. J'ai des envies de mots. Des envies de retrouver ce moment magique où d'une pichenette on fait tomber le premier mot qui entraîne, en réaction en chaîne, le poème, la lettre, la prose, la nouvelle et qui sait... le roman. Ce flot simple, évident, plein de heurts, d'obstacles et de secousses mais dont le seul but, tel un ruisseau de montagne se jouant des courbes de niveau, est d'arriver à la mer, par les méandres des rivières et des fleuves.

J'ai coutume de dire que la lecture est du temps volé. Du temps que l'on n'a pas mais que l'on prend sur tout le reste. Écrire, raconter, bleu-noir sur page blanche, est aussi du temps volé. Mais c'est beaucoup de temps volé. On peut lire à la sauvette, entre la poire et le fromage, dans le bus ou la salle d'attente ou juste avant de s'endormir. Quelques lignes, quelques pages. Écrire, en revanche, demande (me demande) du calme. La plume bleu-noir veut son lot de cigarettes, de musique parfois, de flamme vacillante d'une bougie qui menace de s'éteindre à chaque coup de vent. L'écriture ne supporte pas d'être pressée, de regarder sa montre en se disant qu'il ne lui reste qu'une heure, une minute, une seconde.

Alors je tape. Ici, en passant, rarement, trop rarement. Et j'ai mal au clavier, car il lui manque la rature, la larme qui dissout l'encre et fait d'un "e" un nuage. J'ai la tête trop pleine et ne sais plus prendre le temps, ce temps volé.

"En charge de" me gave. Grave.

Le titre dit tout. Sérieux.

Je vis dans un autre pays. Du coup, je bouffe de l'allemand à la pelle et malgré presque six ans de pratique quotidienne, je continue à faire des fautes plus grosses que moi (je sais pas si vous voyez la taille des fautes...). Mais les joies de l'internet me permettent de garder un lien avec ma langue maternelle. J'ai même acheté une radio "internet" que je balade de ma cuisine à ma salle de bains en passant par ma chambre et grâce à laquelle je "garde le contact". Je lis des blogs et des articles de journaux (pas beaucoup, je sais pas faire) et des tweets et des trucs et des machins, en français dans le texte. Enfin, presque.

Parce que où qu'on se tourne, ce "en charge de" revient, tel un boomerang de la mauvaise grammaire (la mienne, en tous cas). Dans les journaux du matin sur France Inter, dans les journaux du soir sur Europe 1, dans les journaux télévisés de France ou de Belgique (TV5), dans des blogs par ailleurs fabuleusement drôles et à la plume acerbe et belle (oui, belle, j'aime quand on écrit comme je voudrais qu'on me parle). Et ça me gave. Grave.

Je ne sais pas pourquoi. Je suis une adepte du week-end, une inconditionnelle du staff et je passe mes journées sur internet (et pas sur la toile). Mais "en charge de", ça me donne des boutons. Il paraitraît même que c'est un anglicisme, syntaxique même que (dixit Wikipédia, mais comme chacun sait, n'importe qui peut écrire n'importe quoi, dans Wikipédia, donc ce n'est pas une référence). "En charge de" évoque le poids total en charge, une réminiscence du permis de conduire (vous savez, les acronymes dans l'intérieur des portes de voitures ?).

Bref. Chez moi, le "en charge de" ne passera pas. Les ministres seront chargés de (ce qu'ils voudront d'ailleurs), et je filerai des coups de main aux personnes chargées de réaliser [1] une tâche [2] . Point.

Tiens, avec ce post, j'ai dû faire monter les statistiques Gougeule sur "en charge de" [3] et cela ne fait pas probablement pas avancer mon schmilblick.

Peu importe. Je l'ai dit, je me sens mieux.

Notes

[1] D'ailleurs, reste à voir si réaliser n'est pas lui aussi un anglicisme...mais je l'aime bien, celui-là.

[2] Dans le blog sus-nommé, sous le titre "Ce texte ne s'adresse pas à celles qui...", dans un billet qui, ô comble des combles, s'appelle La bonne française et que par ailleurs je trouve fort intéressant

[3] dont les résultats de recherche donnent Haute Autorité de Santé - Prise en charge de l'urticaire chronique comme premier résultat, ce qui devrait en faire réfléchir plus d'un

Wikipedia Is Ten Years Old: A Human Adventure

Wikipedia turned 10 about a month ago. For me, the adventure is about five and a half years old. I started editing Wikipedia in October 2004. I remember how I found Wikipedia, it was through the Firefox Crew Picks at the time, a bundle of links to cool open source/free websites included in the Firefox browser, which was then in its infancy. I remember why I contributed the first time, I found that there was no article about Greta Garbo on the French Wikipedia, which I thought was like "wow, this is an encyclopedia and there's no article about Greta Garbo? That can't be a good encyclopedia." What I don't remember, however, is how I found the edit button. I just found it. I registered right away, and started translating the Greta Garbo article into French from the English article. I had never looked at Wikipedia before, and I don't remember it taking me more than 5 minutes to actually get into the editing part of thing. It was, somehow, rather natural.

From my first edit, everything went very fast. I started editing like crazy, spending nights improving articles, translating a lot, correcting spelling mistakes, fighting vandalism. Very quickly, I ended up in the wikipedia-fr chatroom on IRC, asking here and there about how to edit, how to organize, basically how to go about being part of this adventure. I had no clue about Wikipedia being free content, and frankly, I didn't care. It was fun, and most importantly, it was full of cool humans I could interact with from my little Parisian appartment.

A few weeks into Wikipedia, I got to talk to "Anthere" (Florence Devouard), who was on the board of the Wikimedia Foundation. She asked me what I did for a living, and when I answered "event manager", she said "great! we're looking to organize an international conference, and we have no clue where to start, you're the right person for that". So two weeks into Wikipedia, I was brought into the "organisation", introduced to Jimmy Wales, and asked to help with the organisation of the first Wikimania (the name came later). What was but a virtual adventure became pretty quickly a human adventure. I kept on meeting people, at Fosdem first, then at various international and local meetings. The translation of a virtual world into a real-life world was quite a natural thing to me, as I had been a long-time chatter in other channels and had met a bunch of people on the internet, who had quickly become real life friends through meetings across the globe.

The more I got involved into organizing Wikimania, the less I edited. Parallel to the organisation of Wikimania, I followed the founding of the French chapter, and got more and more involved in the organisational part of things. I also got to understand more about open source and free content. I was very active on Wikimedia Commons at its beginning, as I saw in it probably the greatest achievement of the Wikimedia world. I still think that Wikimedia Commons has a tremendous potential, that is held up by the very thing it is built on, namely the "wiki" part of it. But that is for another debate.

The first Wikimania came and went. I met even more people, and edited even less, but got involved more and more in the organisational development. The Foundation, chapters, all of these things that made the whole virtual part of free knowledge less virtual, were the things that kept me there. And are the things that keep me here today. To me, Wikipedia, and even further, Wikimedia, is primarily a human adventure. That so many people around the world share the same ideal of bringing knowledge to everyone, and work together on making it happen, is the most important thing about Wikimedia. I am dedicated to the mission, but most importantly, I am dedicated to the people, because without the people, there is no wiki, no knowledge and no collaboration. I might not be the greatest contributor in the projects, but I am so conceited as to hope that my work (as staff, as a professional and of course, as a volunteer) has helped the whole Wikimedia ideal come a tiny bit forward.

I am extremely grateful to have been part of this adventure for the past 5 and some years and hope to be part of it for years to come. And I want to thank everyone who is making this adventure possible, because without them, well, you know... Wikipedia and the Wikimedia projects would not have become the resource that they are today.

(This post was in the works, and got finished thanks to the prompt of Dieci anni di sapere (Ten Years of Knowledge) where it was translated into Italian.)

Wikimedia Chapters: We Want to Hire Someone, Where Do We Start? (part II)

This is the second part of a blog post that got way too long to be just one. The first part, which details prerequisites, what Wikimedia chapters do and much more, can be found here.

So I left off at the three possible paths I see to professionalisation of a Wikimedia Chapter. Note that I don't necessarily believe that all chapters should professionalise to start with. But given that a chapter is thinking about it, here are three possible start points I can imagine.

Getting rid of administrative hurdles: The Secretary

The first direction I see is prompted by the growth of administrative burden on chapter volunteers. Whether it comes in the form of donations (lots of tax receipts and accounting to do) or members (keep lists up to date, take money in, prepare General Assemblies), or expense reports (many volunteers doing little events by themselves, sending in their train ticket and other bus ticket to be reimbursed), the administrative burden is the first one that usually becomes too heavy. It is also probably, some exceptions notwithstanding, the most boring part of running an association. When that takes too much of the volunteers time and motivation, the first thing that suffers is programs. Cool activities, outreach and such, which directly pertain to the objective of the chapter, are quickly put in second place, with an enormous guilt feeling. Not because they are not good, but often because the little administrative things have some fear factor engrained in them if you don't do them, as they are often tied with legal requirements that might threaten the survival of the chapter. So the first option is to outsource (here, outsource means take out of the hands of volunteers to a professional) those, in way of hiring a secretary-type person. A good option might be to start with someone freelance, when the workload does not justify having someone full time. The advantages of having a secretary is that all the administrative things are then taken care of professionally, by someone who can be held accountable. The drawbacks is that a secretary usually has little potential of "growing", of becoming more than a secretary, just because it's what they do well and they don't really want to do other things. In the mid term, a secretary might not be enough to ensure the chapter runs smoothly, especially if the potential for growth is important.Note that the secretary-type job might also apply to other areas such as accounting or press relations. Those are quite easily outsourced (this time, not hired in full, but buying a few hours of someone doing this as a freelance).

Supporting members and initiatives: The Project Manager

The second option to get onto the path of hiring someone is that of hiring a Project manager. In chapters wih active members that come up with lots of ideas, one of the bottlenecks might be that those ideas never see the light of day because the logistics or program management aspect of them never gets done. We go back to the "not having time" to do things. Having someone dedicated to implementing ideas might be a good option to make sure that nothing gets forgotten and that the chapter keeps a healthy level of programmatic activities (in direct connection with the objectives of the chapter). Often, events for example, will require some things such as finding a venue, keeping a budget and such, which not all volunteers are ready/able to do. However, without this part, the events just don't happen. Having someone who has an idea of what the timetable should look like, who is able to break down tasks and assign them, is a good way to make sure that as many people as possible see their ideas implemented. It also takes the boring-stressful part of putting together real-life projects which might put off volunteers. It also helps with talking to integrated bodies (such as local institutions, or even suppliers) as this gives them a sense of organisation which might reassure them. A project manager should be comfortable working with volunteers (not always an easy thing) and take the lead on organisational aspects without taking the lead on content aspects (you want to keep your volunteers in a state where they are actually doing something). They should also be comfortable with the very difficult step of making virtual things into concrete things (a particularity of Wikimedia crowds being that they live in a very virtual world and that going "back to earth" may be a difficult step). The advantages of having a project manager is that while not all projects might see the light of day, it is easier for the chapter to prioritize which initiatives they want to carry out by assigning one person to support the volunteers on a particular idea, rather than having only ideas implemented which have enough volunteers to be carried out. The drawbacks is that a real project manager needs projects, otherwise they get bored. They also need a strong management, which is able to give strategic directions as to which projects should be supported and which should not, in short, what the priorities are. And that kind of management takes an awful lot of time on the part of volunteers. On the longer term, the project manager could evolve into say a "program manager" overseeing a little team of project managers. However, I don't think a chapter can go on for ever with just project managers, there comes a point where more management strength is needed, which leads up to my third option.

Starting at the top: The Executive Director

The third and last option I am going to look at here is that of hiring an executive director. If a chapter is big enough (read: has the money), hiring an Executive Director is another option that they might want to consider. The idea being here that you introduce right away someone at the top of the management scheme, who will help the chapter implement its strategic decisions. Their role is then not so much to do things, but rather to have things done by building the chapter staff from scratch, addressing the right issues at the very beginning. This might be an option for chapters which come into a lot of money quickly (obviously, an executive director with the right skills will probably cost more than a secretary), or for those who are willing to invest in the future quickly. Note that I think that any hiring will mean investing in the future, but hiring an executive director right away is a way to push a chapter's volunteer body (the board, mainly) to evolve to a strategic planning role and take them away from the day-to-day business. Hiring an executive director as the first person is a tricky thing, as volunteer boards (in Wikimedia and otherwise) usually have a hard time getting away from the operational side of things. The advantages I see in hiring an executive director is that the chain of command is easier to build on the longer term. Hiring a project manager or even a secretary, and then imposing a manager on top of them is sometimes difficult, especially when they have been working alone for long. An executive director coming in first has the advantage that they can build their team from scratch, and avoid having to "manage" people who are not ready to see someone come and tell them what to do. The drawbacks might be that an executive director as a first hire will have well... nobody to manage. This situation depends on the chapter's means of course, but it might linger until the chapter actually have the means to hire someone else. Starting off with an executive director can also be problematic if the board is not ready to let go of operations, or on the contrary suddenly gives up everything they were doing until then, which might end up in an executive director doing tasks that should be done by others (read: doing the work of a secretary and/or a project manager, among others). An efficient executive director must be empowered from the start, not an easy thing to do.

The more I think about it, the less I know which option has my preference. I've seen all implemented, with more or less success, and I am not sure if I have a preference at all. I guess a project manager might be the easiest to handle as a first hire, simply because you can always have a secretary on an hourly basis if the need really arises, and because I believe that in the end, programs should have the highest priority. This said I believe that a project manager should be hired because they're good at what they do, and not in the light of them becoming an executive director at some point. Of course, it can happen, but managing an office and managing staff and setting up an office are not the same thing, so the project manager should probably be told at the beginning that the next hire might be an executive director.

Note that all of these options are thought up to answer the question of "who should we hire first". In the longer run, if a chapter is to professionalise, I think that all of these people should be part of the staff. Along with, later on, a person specialised in PR, someone to take care of fundraising etc. (which, however, I don't think should be the first hires). Of course, there's always the fourth option, which implies not hiring anyone. I think it's particularly true for Wikimedia that not all chapters will have to professionalise, even in the long run. But I'll talk about this in another post, maybe a part III. :)

one comment

-

I think at some point all chapters will have to hire people, even if it is on a case-by-case basis. You might get lucky and have among your volunteers people who can fulfill the roles of secretary, project manager, etc, but they will be doing so in their spare time, which also means that results (and accountability) may be low, even despite their best efforts. You cannot ask a volunteer to leave their day job and concentrate all of his or her efforts on a non-paid position. That's unfeasable.

This doesn't mean a chapter made up only of volunteers cannot get things done or achieve results. But I think it may take longer and be way more stressful for all involved.

—

On Sunday 13 February 2011 at 15:44

Wikimedia Chapters: We Want to Hire Someone, Where Do We Start? (part I)

To this day, there are around 30 Wikimedia Chapters. Wikimedia Chapters, for those who don't know, are national organisations which purpose is to support the Wikimedia Projects. At this point in time, they are organized along national territories. The oldest Wikimedia Chapter, Wikimedia Deutschland (Germany), of which I am a board member at the time of writing, exists since 2004. It has now an office and around 12 employees. In the constellation of Wikimedia Chapters, it is the only one with such a strong presence of staff at all. Other chapters have hired people, but no other chapter, as far as I know, has more than 3 permanent employees.

I have been observing the development of Wikimedia Chapters for a while now, and I have been thinking a lot about what the best path for professionalization (read: hiring people and setting up an office) might be. I must say that I have no exact solution to the question, but here are three ideas I've come across, and the advantages/drawbacks I see associated with them.

Let me start with a simple question that bears answering before we get into specifics:

What do chapters do?

Chapters are usually non-profits established in a given country, whose general goal is to support free knowledge and/through the Wikimedia Projects (Wikipedia et al.). Their activities vary very much country to country, but here is a list of what a chapter may do:

- fundraising (not all chapters are in a position to do fundraising, but those who are usually offer tax-deductibility and participate one way or the other in the Wikimedia Fundraiser)

- real-life events: chapters may support community meetings, or organize conferences on topics related to free knowledge for example

- outreach: chapters support community members doing presentations about Wikimedia projects in all kinds of settings, they pilot programs to acquire new editors on the Wikimedia projects (students, elderly people...), they explain Wikipedia to children, teachers, librarians, companies, you name it.

- partnerships with local institutions: chapters work hand in hand with national/regional institutions, governements, museums, like-minded organisations etc. to either broaden access to free knowledge,

These, in no particular order, are the four main focus of Wikimedia Chapters. They certainly are not exhaustive, (one could add lobbying, support quality in the Wikimedia projects, technical development of tools to better the Wikimedia projects etc.), but they are, in my opinion, the main activities that may warrant sooner or later the need for staff and an office.

All of those, in the early life of a chapter, are taken care of by volunteers. All Wikimedia chapters to this day are member organisations, and have a board elected by a General Assembly of sorts. The details of how this works are country specific, but on the whole, the existing structures are rather homogenous.

When does a chapter need to professionalize?

Huge question, as a matter of fact, since this will as always vary with how a chapter evolves, what kind of activities it fosters (often driven by what kind of members it has), what kind of financial means it has etc. To cut a long story short, my assessment would be that a chapter needs to professionalize when the load of work is too heavy to be taken care of by volunteers (who, after all, only have a haphazard - if sometimes important - amount of time). More explicitely, I would say that a chapter should professionalize when the balance between doing fun stuff or boring stuff for chapter activities tips in the direction of the boring/stressful. In short, when administrative, accounting, organizing et al. becomes so important that as a volunteer, you feel you are lsoing the connection to whatever ideal/fun stuff brought you here in the first place (in many cases within Wikimedia, this will be contributing to the projects, but it can also be "meeting people", or "organizing cool events", or "challenging your brain", whatever). So first question to ask yourself as a chapter: which direction does the fun/boring-stressful balance tip? Mind you, I am convinced that for everything fun, there must be some boring/stressful, it's part of life, but the balance should stay...well, balanced. So let's say a chapter has decided that there is stuff to be done which the volunteers can't do anymore. How are they going to tackle the professionalizing thing?

Where do we start professionalizing?

Good question. I don't think there is one answer, of course, since there are too many things to be taken into account which could favor one way over another. But in the course of Wikimedia organisational development as I have witnessed it, I end up with three different directions a Wikimedia Chapter could take. And a fourth one which would be, don't professionalize at all (don't hire anyone, don't get an office etc.), which might be the topic of another post. But let's start with the prerequisites.

Prerequisite to professionalisation

Well, that one is an easy answer of sorts.

- First, money. Because hiring someone means that you have to pay them. And to pay them you need money. In the case of Wikimedia chapters, this money might come from incoming donations, grants (from the Wikimedia Foundation or other organisations) or any other legal way of getting money. Without money, forget about hiring anyone.

- Second. A clear list of minimum tasks that you expect your employee to carry forward. This ties in with the following point. Without clearly defining a basic task-list of what your employee should be doing, it's going to be hard to even find anyone.

- Third, a willing body of volunteers who will "manage". Now, managing is a broad subject. But if a chapter is going to have employees, there needs to be some kind of managing body (it can be a person alone) which is going to tell the employee what they should be doing. Mind you, noone should prevent the employees from coming up with initiatives as to what they might be doing, but you need a sense of direction.

Once you have those, there are in my opinion three possible directions a chapter could go on the way to professionalisation, these are defined by the person they might first hire. And I'll detail them in another post, because this one is just too long already.

La lune le jour

Ce matin, ma fille qui a l'oeil fin s'est exclamé : Maman ! La lune !

.

Elle était là, la lune, se découpant sur un ciel bleu d'automne. Comme la joue d'un enfant ou la fesse d'un amant que l'on a envie de caresser du creux de la main.

La photo n'est pas ma lune à moi, mais elle y ressemble fortement.

Source : Daylight Moon © Don LaVange, Licence : CC-BY-SA 2.0

Deux-cent quarante huit kilomètres à l'heure

Ils sont deux, ou dix, ou peut-être même qu'ils sont cent et je suis seule. Ils ont des mots qui les relient. Ils n'ont pas oublié comment on écrit inattendu et n'ont pas besoin de dictionnaire. Ou s'ils en ont besoin, ce n'est pas qu'ils ont oublié, mais parce qu'ils n'ont jamais su. Il paraîtrait que l'orthographe, c'est comme nager, on sait ou on sait pas. Enfin, c'est ce que j'ai décidé. Pendant longtemps, sur les bancs de l'école, qui d'ailleurs étaient des chaises, je corrigeais les fautes de mes camarades de classe au nez et à la barbe de Madame J. (vraie, la barbe) lors des dictées en cours de français. Et aujourd'hui, je fais des fautes ridicules que je ne vois plus.

Ici, les phrases sont à l'envers et les mots tellement longs qu'ils font un peu peur. Je me rends compte que je dis les choses au moins deux fois. Une fois dans me tête pour mettre les mots dans le bon ordre. Je joue dans ma tête avec les mots comme ma fille joue avec une pièce de puzzle et essaie de combler les trous. Sauf qu'au contraire d'elle, je n'ai personne à qui demander d'un air innocent si "ça rentre", comme elle le fait tout en sachant pertinemment qu'elle a forcé et que donc, non, ça ne rentre pas.

Ils sont cent, ou dix, ou peut-être deux. Ils ont des vies plus ou moins longues et troublées, des histoires sordides que d'autres ne leur envient pas ou au contraire des histoires magnifiques de couleurs et de vent dans les cheveux et de sourires dont tous sont jaloux. Je suis seule et j'écoute Anne qui chante, "que tu sois l'une ou l'autre, souvent la marche est haute, pour trouver le bonheur". Je ne suis ni l'une, ni l'autre, je suis moi et là tout de suite, alors que le train avance de tunnel en verts paysages à deux-cent quarante-huit kilomètres à l'heure, j'ai envie de pleurer sans raison. Peut-être aussi parce qu'Anne raconte l'histoire de Lazare et Cécile et que de toutes façons, cette chanson m'a toujours bouleversée à en rire et pleurer à la fois.

2 comments

-

merci, notafish, d'avoir ach'té mon Grand paradis!... Je ne connaissais pas votre blog, et j'aime bien, j'aime aussi la façon dont vous écrivez. Vous êtes en Allemagne, c'est ça?

—

On Sunday 10 October 2010 at 18:14 -

Bonjour Angélique,

Merci à vous d'avoir visité ces pages :). Oui, je suis en Allemagne. Une expat de plus ;).

—

On Monday 11 October 2010 at 15:02

Everything He Sees

2 comments

-

Woah !

—

On Wednesday 22 September 2010 at 12:00 -

I love this image!

Hope to see you and your 2 little kids soon :)—

On Wednesday 22 September 2010 at 18:01

Quelle belle verité... Et si on lui écrivait toutes une belle carte à madame P. et qu on y ajoutait les dessins de nos enfants! Elle l'a vraiment mérité! [edit du nom :)]